Thoughts

Feeding The Moloch: On Crisis, Speculation and Public Housing Renewal in Victoria

This paper explores the "feeding of the Moloch" that is the housing crisis in Australia. It argues that the crisis is the result of decades of neoliberal policies, speculation, and the dismantling of public housing. The paper examines the Victorian government's Public Housing Renewal Program (PHRP) and critiques it for its lack of evidence based policy, focus on social mix, and failure to address the crisis. Additionally, the paper critiques the speculative nature of the housing market and the government's inaction. It concludes by calling for architects to take action and contribute to solving the crisis.

On Crisis

It is widely acknowledged that Australia, similar to many countries in both the Global North and Global South, is currently witnessing an acute ‘housing crisis’. However, the crisis in Australia has been building to a cataclysmic-like pressure point for the better part of two decades, arguably under the successive neglect of governments. As of July 2023, the situation seems dire; the national vacancy rate is 0.9%. The demand for affordable, accessible housing far outstrips supply in our capital cities and regions, and the twin spectres of inflation and stagnant wage growth further induce housing stress on all tenure groups. Australian housing prices are both overvalued and unaffordable. The ratio of house prices to incomes and rents in Australia is at the highest in OECD countries since 2003. By late 2021, Australia's median national house price to income ratio had ballooned to 12.1, compared to 5.1 in the UK and 5.0 in the US. This is despite both comparable Anglocentric countries suffering their unique housing crises. As many argue, an inability to access secure affordable housing is the main driver for inequality in Australia. At the same time, as the crisis worsens, the most significant intergenerational wealth transfer in the country's history shows signs of cementing a two-tier class-based status quo between those who can and cannot access housing.

Australia’s relationship with housing since colonisation has been deeply problematic. Longstanding colonial practices premised on terra nullius not only continually reject Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples epistemological perspective but actively engage in systematic erasure, displacement and dispossession of sovereign First Peoples' rights and connection to Country. By extension, the cadastral property system as a colonial invention has been the dominant tool by which the colonisation of Australia has been enacted, coupled with repeated ongoing violent enforcement of hegemonic power. Fundamentally, how property is framed as part of the settler myth-making of ‘Australia’ continues to reject ancient and enduring pre-settler systems of law and further disenfranchises First Peoples. It is a lamentable case in point that concerning the housing crisis, a 2022 AHURI report into Indigenous homelessness found the Indigenous homelessness rate is ten times that of non-Indigenous people, with one in 28 Indigenous people homeless at the time of the 2016 census. Furthermore, the report found that "a continuity of dispossession, racism, profound economic disadvantage and cultural oppression shapes the lived experience of many Indigenous Australians today". The 2021 Census found that 1 in 5 of those experiencing homelessness were Indigenous. Indigenous housing is a crisis-within-a-crisis and a long-existent symptom of the wider neo-colonialist housing policy setting we find in Australia.

'DeFlat' Kleiburg, Amsterdam, NL by NL Architects + XVW Architectuur, 2011-2016. Photo: Marcel van der Burg.

Dismantling Public Housing Renewal

Decades of overtly neoliberal sympathetic and populist vote-buying public policy have created the perfect storm in the form of a perpetually propped-up speculative housing bubble. In what we might consider civil society, long gone are the utopian Menzies-era ideals of housing for all as espoused by the embedded liberalism of the Keynesian post-war period. Construction of new public housing dwellings is currently at its lowest rate in over 40 years. Existing public housing stock is chronically underfunded and endures an ongoing excruciating demise. In the Australian context, the legacy of ‘The Pruitt-Igoe Myth’ continues to reverberate in policy-making echo chambers. At the same time, there are concerted and ongoing efforts by state governments to shed direct responsibility for public housing through privatisation and aggressive asset transfers under the guise of ‘public housing urban renewal’ programs. Championed by advocacy coalitions comprising (but not limited to) state governments, private developers and more recently, not-for-profit Community Housing Providers (CHPs).

In Victoria, renewal programs such as the Public Housing Renewal Program (PHRP), in particular, have been criticised as fundamentally flawed for several reasons. Examples including a project brief that is premised on the paternalistic presumption of the benefits of ‘social mix’. Colloquially referred to in the property industry as the ‘salt and pepper’ approach to social housing. The non-evidence-supported strategy of co-locating social housing tenants with their ‘better off’ private market renter/owners aims to achieve social capital transfer and foster a ‘community’ amongst different socio-economic demographics. Critically, we must analyse ‘social mix’ agendas against the problematic yet dominant historical backdrop of Antipodean assimilation and forced Anglo-Saxon homogeneity. Regarding functionality and programme, despite PHRP projects seeking to ‘renew’ public housing stocks, there is a lack of demonstrated significant improvements to housing stocks. For example, the Victorian ‘Big Build’ housing projects that fall under the PHRP program generally mandate a minimum 10% increase in social dwelling numbers yet result in an overall reduction in the total number of beds per dwelling compared to existing demolished project stock. In this example, adding additional private ‘market’ rental stock or the inclusion of the minimal number of ‘affordable’ dwellings as part of the overall project does little to offset the demolition of existing public housing stock, the fracturing of existing communities and displacement of residents (regardless of their ‘rights of return’) once the projects are completed, to say nothing of the significant sustainability concerns such tabula rasa methods employ.

Transformation of 530 dwellings, Block G, H, I, Grand Parc Estate, Bordeaux, France by Lacaton & Vassal, 2017.

Photo: Philippe Ruault.

Contemporary States of Speculation

The state itself, as the principal actor in the housing space, has more incentive to maintain political and economic order than try to solve the ongoing crisis, evidenced most recently by the lack of substantive policy in the recent 2023-2024 Federal and Victorian State budgets. Despite the historical performance of the initial Commonwealth-State Housing Agreements (CSHA), consider, for example, that the first 10-year CSHA was able to build nearly 100,000 public housing dwellings between 1945-1955 alone. There seems little appetite to revive the commonwealth's role in affordable housing delivery. The only signature federal policy is the nebulous $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF) with the somewhat opaque goal to “fund acute housing needs on an ongoing basis” and build 30,000 new social and affordable housing in its first five years, albeit with the caveat that expenditure is dependent on the fund itself making returns, essentially taking a wager on the ASX and continued economic growth. Even at the level of federal public policy, actions seem entirely couched in the notion of Australia as the ‘lucky country’, despite the housing crisis in Australia as an exemplar of free market failure in providing a basic necessity; the human right to adequate housing, for the Federal government it’s a case in point of a better tomorrow, tomorrow.

With recent discussion of the housing crisis showing no sign of exiting the news cycle, National Cabinet has agreed to boost the 2022 National Housing Accord target from 1 to 1.2 million new homes for the period 2024-2029. At the same time, National Cabinet has flagged a ‘National Planning Reform Blueprint’, targeting what it sees as dysfunction in local and state planning policies. When the political messaging of a complex issue is simplified to ‘insufficient supply’ and ‘bureaucratic red tape’, panacea solutions seem to have rational appeal, yet only time will tell how this will be achieved without a tangible and nuanced delivery pathway. Finally, moves by the National cabinet to strengthen tenancy laws would be a positive signal if those laws weren’t already legislated in most states, becoming, at worst, a cost-free quick political win for the Federal government and, a best, a PR mechanism to help build appeal for the emerging Build To Rent (BTR) sector tied so heavily to domestic and international institutional wealth.

The resulting instability of a developed economy continually relying so heavily on its property sector creates a situation where speculative property ownership (thinly masked under the auspices of “the great Australian dream”) creates a “too big to fail” relationship between homeowners, financial institutes and elected governments. This is even though homeownership rates are in decline, having peaked between the 1940s-70s and having slumped to 67.1% in recent years. We see the ongoing demonisation of other tenure models such as private renting or social renting in lieu of the lavishly praised ‘home owner’, here ‘Howards Battlers’ are lionised whilst those who find themselves long-term renters (regardless of demographic) are considered abject failures, those trying to access social housing; particularly public housing are stigmatised as ‘less than’. The 'Hegemony of tenure' prioritises homeowners in policy-making, portraying home ownership as moralistically superior and housing as a speculative asset rather than a basic human need or infrastructure. The ‘reverse welfarism’ of Australian housing policy undermines legitimate attempts to de-escalate the crisis and continues to privilege the landlord class while sacrificing society.

In contrast, it would be helpful to consider the different perceptions of Viennese housing policy. In the Austrian context, 40% of houses are of rental tenure. In what has come to be labelled the ‘affordable housing Mecca’ of Vienna, this number rises to an incredible 80% of dwellings in rental tenure. This is backed not just by one of the world's largest public (and affordability-regulated) rental housing systems but a local policy and media setting where the rights of rental tenure are at the forefront of political debate and enshrined in law.

The vast majority of Australians (even long term-renters) have been coaxed to view housing as a speculative asset (a non-productive one at that) rather than to conceptualise housing as a fundamental right for all. Richard Denniss, economist and director of The Australia Institute, applies the useful metaphor of the current housing crisis as a kind of ‘Kabuki Theatre’, in particular reference to the recent push in Governmental language for ‘making housing affordable’. It may seem reductionist, but the fundamental core issue in the Australian housing crisis is not a total lack of supply; instead, house prices are simply too high. If public policy isn’t making prices fall, then those policies can’t make things more affordable. What could be more Helleresque?

Property ownership here, particularly in our charged media landscape, is not framed as ‘building a home’ as much as a rush to ‘get on the property ladder’ that paradoxically only lets you ascend the rungs, less the whole house of cards comes crashing down. Here to quote researcher Chris Martin of UNSW’s City Futures Research Centre, the property investor is cast as the self-made ‘clever Odysseus’ who achieves self-realisation and ‘financial freedom’ by harnessing the transformative leverage of property ownership. The hegemony of this discourse cannot be dissuaded. It permeates throughout any housing conversation. Those without the social, financial or cultural capital to enter the housing market are stigmatised, at best, patronised as ‘uninformed’ youths or those who ‘missed the boat’ of favourable financial conditions. At worst, paternalistically as ‘undeserving’ of adequate housing due to their perceived individual moral failings; vocally, these might be expressed along classist lines of employment, education or welfare reliance. More insidious biases quietly voiced abound along racist, sexist, ableist or ageist lines.

The culture of home ownership in Australia is both manufactured and politically expedient. To malaprop an idiom, the best time to buy a home was thirty years ago. The next best time is today. For many, the family home (safely not included in current aged pension asset tests) is considered the quintessential Australian retirement nest egg. When the time comes to leave this mortal coil, this asset class becomes the primary driver of the intergenerational transfer of wealth. Here we see the antithesis of the Chinese proverb, “One generation plants the trees, and another gets the shade.” Sexual morality and ascetic aspirations aside, we perhaps shouldn’t be surprised that the Catholic church introduced clerical celibacy laws in response to the potential for the concentration of wealth in the form of ecclesiastical property being passed down clerical lineages. As impolite as it may be to say out loud, the corrosive and divisive nature of this en-masse intergenerational transfer of wealth cannot be understated, and is in itself a serious threat to a better future for Australia.

The Speculative and/or Ethical Architect

There is a secondary ethical crisis for architects and other design professionals involved directly in providing housing (affordable, social, speculative or other). Are our professional and personal actions directly contributing to and exacerbating the crisis? Manfredo Tafuri's comments related to the Progetto di crisis seem relevant once more:

“Utopias don’t exist anymore. Engaged architecture, which I tried to make politically and socially involved, is over. Now the only thing one can do is empty architecture. Today, architects are forced into either being a star or being a nobody. For me, this isn’t really the “failure of modern architecture”; instead, we have to look to what architects could do when certain things weren’t possible and when they were.”

Indeed, it isn’t good enough to merely greenwash our latest architectural projects in a vain attempt to win accolades whilst ignoring the underlying instrumentalism of our professions to capitalism's corrosive social effects. Suppose architecture has completely surrendered itself to the post-political, as some have argued, might there be any minor redemption arc for the discipline, particularly in the Australian context and in light of the ever-worsening crisis? Is there a space for architects to more critically assess and actively advocate for housing policy reform? Here I am reminded of the lamentable recent anecdote of a senior public servant (and former architect) commenting there was “no role for politics in architectural work”, eviscerating their credibility as a prominent paid advocate in both spheres of work.

Arguably, Australia (and Victoria in particular) indeed has a rich legacy of architects attempting to ‘make political’ issues relating to housing, be it Robin Boyd's twin aesthetic/Australian ethos critique of the banalities of suburbia in The Great Australian Ugliness (1960) or his work with the Small Homes Service (1947-1953), which sought to advocate for the common good through the delivery of modest, environmentally sensitive, affordable and accessible home designs. Another example would be prolific Architectural historian Miles Lewis’ prominent advocacy role concerning the Carlton Urban Renewal Scheme (1972) and ongoing participation with other so-called ‘trendies’ in community opposition to inner and middle suburban development they deemed contextually destructive. With architect Maggie Edmonds there is the example of her RAIA-endorsed alternative plan to the Brooks Crescent redevelopment, which sought preservation, rehabilitation of houses, building new dwellings and inclusion of community facilities such as a kindergarten and creche (what Delores Hayden might call a more care-driven approach) to show that retention and renovation of existing housing stock was not only possible but provided for a desirable alternative way forward.

St Georges Road Infill Housing. Photo: Gregory Burgess.

We should reflect on Architect John Devenish's experimentative work heading the Victorian Ministry of Housing infill housing program (1982-1985), which sought to purchase existing housing stock and, through local architectural practices, restore them in an urban contextually sensitive manner, directly attempting to address the bubbling social stigma attached to social housing and public housing bodies. Even if this was tied directly to the Ministry's institutional renewal and repositioning of Public Housing as a temporary stepping stone to home ownership, an essential talking point to the eventual dismantling of public housing. The program’s distinctly postmodern approach is directly inspired by the successful efforts of the Berlin Internationale Bauausstellung IBA (1979-1989).

In more recent years, we’ve seen the Office of the Victorian Government Architect (OVGA) run a series of design competitions and pilot projects (Living Places, Habitat 21 and Future Homes) seeking to present alternative housing strategies and provide a platform for professional discourse in light of the ongoing broader housing market failure. Finally, there is OFFICE, a not-for-profit design and research practice that proposed an alternative ‘Retain, Repair, Reinvest’ model for the Ascot Vale Estate and Barak Beacon Estate. The latter now sadly demolished under the previously discussed State governments Public Housing Renewal Program (PHRP) despite public protest and occupation of the site reminiscent of the 2016 Bendigo Street housing dispute.

Replicable apartment proposals by Design Strategy in collaboration with IncluDesign win Victoria’s Future Homes competition. The Future Homes Project © Design Strategy Architecture + IncluDesign, 2020.

The examples given here are few, but there are many more historical examples of practising architects (some memorialised, others forgotten in the local architectural canon) utilising their knowledge, skills and networks to facilitate positive change in the face of the emerging housing crisis. The solutions to the housing crisis itself are not unknown. Particularly in the last decade or so, there has been an extensive academic focus on the emergence of the nature of the crisis and pathways toward fundamental change. See, for example, the Transforming Housing Project (2014-15), which outlined several policy, investment and demonstration projects supported by a litany of research and case studies or the recently published Housing Policy in Australia: A Case for System Reform (2020) which outlines the historic policy setting which has fueled the crisis along with significant commentary for potential systematic overhaul. The potential for this plethora of earnest and, importantly, evidence-based policy reforms is stymied by a lack of political will. If this cannot be successfully challenged, how can we achieve a future housing condition predicated on equity, intensity and densification of our cities?

Despite repeated calls for reform by policy advocates, little has been done to unwind the overheated speculative nature of Australia’s institutionalised housing sector. There seems to be a dwindling of architectural conviction in confronting the speculation fueling the housing crisis in recent years, both in action and advocacy discourse. Could this reflect the privileged position of the Australian architectural industry's dominant voices? For many industry luminaries, the conditions behind Australia’s housing crisis have benefited them, as they have turned their architectural savvy and social capital into capital accumulation and, by extension, increased wealth and clout.

If architecture itself is indeed post-political, as some suggest, then does that reduce the profession's force majeure role to merely myopic aesthetic criticism? Architecture as a profession has a long tradition of identifying with our patron clients while distancing ourselves from those that cannot afford that same patronage, not to mention a torrid institutionalised legacy of exploitation within practice and the academy. In this respect, the architect's often classist position is not beyond scrutiny or reproach in the context of the ongoing and intensifying housing crisis. Is the limit of our civic engagement that we might sometimes seek to design a seemingly ‘democratic’ institution or public building, putting the literal facade of civility on chimaera-like neo-colonial institutions operating in previously discussed contested settler spaces? Is the future of architecture as a profession in regard to the Australian housing crisis just the ongoing proliferation of Tafuri’s ‘empty architecture’, or can we find a way back to contributing to that quasi-utopian ideal of politically and socially ‘engaged’ architecture that supplants the current ‘Kabuki Theatre’ of crisis?

-

Banner, Stuart. “Why Terra Nullius? Anthropology and Property Law in Early Australia.” Law and History Review 23, no. 1 (2005): 95–131.

Benson, Eleanor, Morgan Brigg, Ke Hu, Sarah Maddison, Alexia Makras, Nikki Moodie, and Elizabeth Strakosch. “Mapping the Spatial Politics of Australian Settler Colonialism.” Political Geography 102 (April 2023): 102855.

Blunt, Alison, and Robyn M. Dowling. Home: Key Ideas in Geography, 2nd ed. London; New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2022.

Burke, Terry, Christian Nygaard, and Liss Ralston. “Australian Home Ownership: Past Reflections, Future Directions.” AHURI Final Report. April 2021: 58-63.

Burns, Karen, and Paul Walker. “Publicly Postmodern: Media, Image and the New Social Housing Institution in 1980s Melbourne.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 32, Architecture, Institutions and Change, 68-81. Sydney: SAHANZ, 2015.

Capp, Ruby, Libby Porter, and David Kelly. “Re-Scaling Social Mix: Public Housing Renewal in Melbourne.” Journal of Urban Affairs 44, no. 3 (2022): 380–96.

Chong, Fenneen. “Housing Price and Interest Rate Hike: A Tale of Five Cities in Australia.” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16, no. 2 (2023): 61.

Cook, Julia. “Keeping It in the Family: Understanding the Negotiation of Intergenerational Transfers for Entry into Homeownership.” Housing Studies 36, no. 8 (2021): 1193–1211.

Daley, John, Brenan Coates, and Trent Wiltshire. “Housing Affordability: Re-Imagining the Australian Dream.” 2018.

Frazee, Charles A. “The Origins of Clerical Celibacy in the Western Church.” Church History 57 (1988): 108.

Groenhart, Lucy, and Terry Burke. “Thirty Years of Public Housing Supply and Consumption: 1981– 2011.” AHURI Final Report no. 231. Melbourne: Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, 2014.

Gurran, Nicole, and Peter Phibbs. “Are Governments Really Interested in Fixing the Housing Problem? Policy Capture and Busy Work in Australia.” Housing Studies 30, no. 5 (2015): 711–29.

Hall, Bianca. “‘They’ll Have to Carry Me out’: The Residents Fighting to Save Their Public Housing Estate.” The Age. March 19, 2023.

Hansen, Amelia. “Exploring the Shortage of Specialist Disability Accommodation in Australia.” Maple Services. March 1, 2023.

Hayden, Dolores. “What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work.” Signs 5, no. 3 (1980): 170–87.

Hyde, Rory. “What Would Boyd Do?: A Small Homes Service for Today.” Architecture Australia 3, no. 107 (2018): 71–73.

Kolovos, Benita. “Victoria’s Social Housing Stock Grows by Just 74 Dwellings in Four Years Despite Huge Waiting List.” The Guardian. March 16, 2023.

Langton, Marcia. “Law: The Way of the Ancestors.” January 2023: 16-21.

Legislative Council Legal and Social Issues Committee (Vic). Inquiry into the Public Housing Renewal Program: Report. Melbourne: Parliament of Victoria, June 5, 2018. https://apo.org.au/node/175096.

Madden, David J., and Peter Marcuse. In Defense of Housing: The Politics of Crisis. London; New York: Verso, 2016, 119-120.

Martin, Chris. “Clever Odysseus: Narratives and Strategies of Rental Property Investor Subjectivity in Australia.” Housing Studies 33, no. 7 (2018): 1060–84.

Martin, Chris. “Security and Renewal in Australian Public Housing: Historical Representations and Current Problems.” Urban Policy and Research 39, no. 1 (2021): 48–62.

Nygaard, Christian, Simon Pinnegar, Elizabeth Taylor, Iris Levin, and Rachel Maguire. “Evaluation and Learning in Public Housing Urban Renewal.” AHURI Final Report, no. 358 (July 2021).

OFFICE. “OFFICE – Retain Repair Reinvest.” Accessed May 28, 2023. https://office.org.au/project/retain-repair-reinvest/.

Parliament of Australia. “Housing Australia Future Fund Bill 2023.” Text. Australia. Accessed May 28, 2023.

Pawson, Hal, Vivienne Milligan, and Judith Yates. Housing Policy in Australia: A Case for System Reform. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2020.

Peverini, Marco. “Grounding Urban Governance on Housing Affordability: A Conceptual Framework for Policy Analysis Insights from Vienna.” Partecipazione e Conflitto 14, no. 2 (2021): 848–69.

Porter, Libby, and David Kelly. “Dwelling Justice: Locating Settler Relations in Research and Activism on Stolen Land.” International Journal of Housing Policy (2022): 1–19.

Tafuri, Manfredo. Interview with Richard Ingersoll. “Non c’è critica, solo storia.” Casabella no. 619-620 (1995): 98.

Tedmanson, Deirdre, Selina Tually, Daphne Habibis, Kelly McKinley, Alwin Chong, Ian Goodwin-Smith, Skye Akbar, and Kate Deuter. “Urban Indigenous Homelessness: Much More than Housing.” AHURI Final Report, no. 383 (August 2022).

Visontay, Elias. “Living with Density: Will Australia’s Housing Crisis Finally Change the Way Its Cities Work?” The Guardian. April 15, 2023.

White, Iain, and Gauri Nandedkar. “The Housing Crisis as an Ideological Artefact: Analysing How Political Discourse Defines, Diagnoses, and Responds.” Housing Studies 36, no. 2 (2021): 213–34.

Available in Inflection Vol. 10 “Housing”

This paper explores the "feeding of the Moloch" that is the housing crisis in Australia. It argues that the crisis is the result of decades of neoliberal policies, speculation, and the dismantling of public housing. The paper examines the Victorian government's Public Housing Renewal Program (PHRP) and critiques it for its lack of evidence based policy, focus on social mix, and failure to address the crisis. Additionally, the paper critiques the speculative nature of the housing market and the government's inaction. It concludes by calling for architects to take action and contribute to solving the crisis.

An Exploration of Architectural Temporality

The notion of temporality within architecture is rarely one that is given considerable thought beyond utilitarian aspects of durability, or the notion of architecture as a form of momentary ephemeral spectacle. This thesis sought to explore ways of designing with temporality in mind to help imbue architecture with a more humanistic and experiential nature.

The thesis was comprised of two parts; the first a condensed survey into architectural approaches and writings on the nature of temporality, the second comprises a design project which attempts to utilise the research ideas in generating a temporal architecture that combines permanence, duration and ephemera into an experiential architecture of place. This thesis extract encapsulates part one only.

“What is time? A secret — insubstantial and omnipotent? A prerequisite of the external world, a motion intermingled and fused with bodies existing and moving in space? But would there be no time, if there were no motion? No motion, if there were no time? What a question! Is time a function of space? Or vice versa? Or are the two identical? An even bigger question! Time is active, by nature it is much like a verb, it both “ripens” and “brings forth.” And what does it bring forth? Change! Now is not then, here is not there — for in both cases motion lies in between. But since we measure time by a circular motion closed in on itself, we could just as easily say that its motion and change are rest and stagnation — for the then is constantly repeated in the now, the there in the here. . . . Hans Castorp turned these sorts of questions over and over in his own mind.”

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, p. 339. 1

Philosophies of Time

“What, then, is time? If nobody asks me, I know;

St. Augustine of Hippo, Confessions, Book XI. 2

There is perhaps no quote more relevant than St. Augustine’s when commencing the task of trying to understand or even simply define what exactly ‘time’ is. As finite creatures we take for granted its omnipresence in all aspects of life and tend to ignore the somewhat abstract concept where possible. In a simplistic way we may accept that time refers to the procession (ostensibly irreversible) of one event after another in a seemingly infinite succession of change. Time becomes the absolute condition which all events are part of as comparison to the subjectivation of time which is the creation of memory. That such an intangible infinity permeates all aspects of our perceived reality is such a powerful concept that it has enticed philosophic inquiry since antiquity, the curious mind seeks what it does not know; by extension we can never really ‘know’ time. The task of trying to understand time has led to an ever-complex bifurcation of enquiry and differing ideas that cast a long shadow on the development of culture, religion and scientific endeavour.

To butcher a Donald Rumsfeld quote, we can see how it may fall to the realm of the philosopher to try to know the known unknown of time. As with most concepts explored (and constrained) in Western philosophy, the long arrow of history can trace ideations on time back to the Athenian schools. Of great interest and debate to the Greeks was the ‘Paradox of Time’ put forward by Zeno of Elea which related the change inherent in time to the illusion of motion, a claim strongly refuted in Aristotle’s Physics (350 B.C.E.). Aristotle directly differentiates between ‘movement’ and ‘change’ and gives his definition of time as: “The measure of change with respect to before and after.”3

Jumping forward almost two millennia to what we might consider the ‘modern’ hegemonic cannon of philosophical temporal inquiry, we see Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781) time comes to occupy a similar definition as that of space, with space being the pure form of ‘external intuition’ and time coming to be the universal condition of both immediate internal and mediate external phenomenon.4

In Heidegger’s Being and Time (1927) the nature of time is inherently existential and directly relates to the finite human. In this way time for Heidegger is the measure of what can be done by man regarding this finitude. Heidegger goes to lengths to show that time is always a directed concept, as is ‘it is time for’. To ‘dwell’ in time for Heidegger is to confront the finitude of existence.5 With Freud, as is almost always the case, the unconscious is defined by a notion of ‘timelessness’. The relation between Freuds ‘psychic apparatus’ of the unconscious, preconscious, conscious and topographic see time as the record of transportation or ‘registration’ of one notion from one system to another.6

Deleuze and Guattari see philosophical time in a ‘straitigraphic ’ sense, with before/after forming an order of superimposition on what they call ‘the plane of immanence’ which puts it in conflict with their notion of scientific time, that is, the bifurcating notion of scientific progress in a sequential order.7 The relationship between ‘time’ and ‘history’ is an equally nebulous topic as American art historian George Kubler summarises:

“Without change there is no history; without regularity there is no time. Time and history are related as rule and variation: time is the regular setting for the vagaries of history.” 8

British anthropologist Tim Ingold counters this:

“Let me begin, once again, by stating what temporality is not. It is not chronology (as opposed to history), and it is not history (as opposed to chronology). By chronology, I mean any regular system of dated time intervals, in which events are said to have taken place. By history, I mean any series of events which may be dated in time according to their occurrence in one or another chronological interval.” 9

The notion of the role of time with regards to modernity is of particular interest. Consider for instance American historian Lewis Mumford’s insistence within the seminal Technics and Civilization (1934) that the ushering in of modernity is directly tied to the invention of the clock and thus by extension the production of the ‘second and minute’ has become a quasi-tangible manifestation of time. This machine becomes the prototype which enables the creation of all machines to come to rely upon. For Mumford mankind:

“Could do without coal and iron and steam easier than it could do without the clock.” 10

In The Culture of Time and Space (1983), American historian Stephen Kern studies how the changes in thinking about abstract philosophical categories of time become manifested in a concrete historical situation. According to Kern:

“From around 1880 to the outbreak of World War I, a series of sweeping changes in technology and culture created distinctive new modes of thinking and experiencing time and space. Technological inventions including the telephone, wireless telegraph, x-ray, cinema, bicycle, automobile, and airplane established the material foundation for this reorientation; independent cultural developments such as the stream-of consciousness novel, psychoanalysis, Cubism, and the theory of relativity shaped consciousness directly. The result was a transformation of the dimensions of life and thought.” 11

Philosopher and architect Christian Hubert summarises this notion of history, modernity and time neatly:

“Modernity must be understood as an attitude about time, as a sense that the present differs qualitatively from the past, and that the future is what counts.” 12

These are but a few different philosophies of time, some are interlinked, some in complete opposition and antithesis to one another. It is but a small spattering of the multitude of ideas and frameworks for ‘time’ put forward by some of the greatest thinkers of history. Not to even mention the evolving nature of ‘scientific’ time, from antiquity through to today. From the Greek notion regarding time as an illusion to Copernicus’s heliocentrism, Newtons reversible Newtonian time, Einstein’s relative time and even to current theories of unified space-time.

It is not wrong to say that the referenced philosophies are in the majority from a surface level reading of the canon of Western philosophy, however, with the global proliferation of the modernist movement from the 18th century onwards and concreted by the homogenised architectural ‘supermodernity’ in our 21st century age of perpetual crisis, this understanding of ‘temporality’ has come to be the hegemonic conceptual in the architectural discourse of time. Although increasingly an acceptance and exploration of epistemologies related to philosophies of time have opened up great avenues and departures from the assumptions and preconditions of Western philosophy, there is still a great and perpetual endeavour to be undertaken by philosophers and laymen alike in trying to understand the fundamental question: What is Time?

On Kawara, ‘1966’, (1966)

Building Against Time

“Time conquers all things . . . all-conquering, all-ruining time….God help me, I sometimes cannot bear it..”

Leon Battista Alberti, De Re Aedificatoria

(“on the Art of Building”), Book I.13

An architect and theorist, Juhani Pallasmaa communicated in The Space of Time (1998) the overwhelming power that time has over us, and by extension our architecture:

“Time is the dimension of experience that is most frightening to us in its seemingly absolute power over us. We feel helpless in relation to time, and we find ourselves at its mercy. As human’s understanding of time lost its primordial cyclical nature, time became linear with an irrevocable beginning and end. We can shape matter and order space, but we cannot throw time of its predestined course. Human’s greatest desire, therefore, is to halt, suspend and reverse the flow of time. Architecture’s fundamental task, to provide us with our domicile in space, is recognized by most architects. However, the second task of architecture, to mediate human’s relation with the fleeting element of time, is usually disregarded.” 14

As with other phenomenologist practitioners Pallasmaa’s views on time and architecture are quickly read as humanist in nature. However, he hints that this second task, that of engaging with the nature of time and its relationship with both the human and their architecture is something which is not eagerly embraced or addressed by architects. The exaltation of an architecture that embraces duration and change is identified by Pallasmaa as lacking. Pallasmaa goes on to talk about the power of architecture of a time (in the Heideggerian sense) to communicate across the ages as a form of time-capsule of Zeitgeist:

“The temple of Karnak takes us back to the time of the pharaohs, whereas the Medieval cathedral presents us the full color of life in the Middle Ages. In the same way, great works of modernity preserve the Utopian time of optimism and hope; even after decades of trying faith they radiate an air of spring and promise. The Paimio Sanatorium by Alvar Aalto is heartbreaking in its radiant belief in a humane future and in the societal mission of architecture. Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye makes us believe in the union of reason and beauty, ethics and aesthetic. These works do not symbolize optimism and faith; they actually awaken the sprout of hope within us.” 15

Eduard Hildebrandt, ‘View of the Ruins of the Temple of Karnak’, (1852)

The notion that ‘time will tell’ is often the hallmark catch-cry of those who seek to judge the intrinsic value of a work of architecture. On one end of the spectrum this relates to what can be called ‘Timeless’ architecture, that which carries on a profound symbolic or cultural meaning much longer than intended. This however does not mean that it escapes or transcends time all together but rather as architectural critic Paul Goldberger states in Why Architecture Matters (2009):

“[Timeless architecture] may have qualities that transcend the immediacy of its moment, and it may communicate eloquently to people living in different times from the one in which it was created.” 16

Ostensibly, within architecture this is done by a seeming rejection of time, by manufacturing a façade of immortality. Timeless architecture does not explicitly position its perceived value through its tectonics yet they serve the purpose of emphasising a presumed infinite and immutable reality of the object, which we know can never actually be true of any artefact. If time is essentially a field of sequential change, then an object which does not seem affected by this state is assumed to be ‘outside’ of the grasp of time, a form of immortality that would be anathemic to any self describing neo-fluxist.

For Vitruvius the fundamental criteria for the judgement of architecture lay within his oft extolled ‘firmitas, utilitas, and venustas’. 17 For Vitruvius it was one matter to state how something can or should be built and another altogether on how he judged the quality of a singular work.

Quality for Vitruvius was not limited to rigid notions of structure, or purely based upon functionality. Rather, it also meant its intrinsic aesthetic quality; for lack of a better word, it’s beauty. Vitruvius listed the ways in which a piece of architecture in its own way comes to embody an aesthetic of timelessness, that being through order, arrangement, eurhythmy, symmetry, propriety and economy. These physical aspects of a design would stand in for those aesthetic abstractions related to the value of an architecture.18

If Vitruvius outlined a criteria for the judgement of the value of architecture, then it was the 15th century Italian architect and polymath Leon Battista Alberti that called for an architecture of permanence. Alberti’s role in the formation of the architect as author, and by extension architecture as its own profession separated from the notions of master-builder are well known. However, it is within his own response to Vitruvius' treatise on architecture that laid the foundation for what has been the dominant mindset for architecture for more than half a Millennia.

In Alberti’s habitus for architecture to be ‘truly great’ it must be complete and unalterable from inception and to the point of the original completion of drawings and models. That the construction which would follow would conform to every aspect of this ‘perfect’ design and every detail within. Building upon this he put forward the influential idea that a building’s perfection was directly tied to its immutability, and any change or revision would irreversibly undermine, alter or destroy that beauty. 19 He summarises this notion succinctly in one passage from his treatise On the Art of Building (1485):

“That reasoned harmony of all the parts within a body, so that nothing may be added, taken away, or altered, but for the worse. It is a great and holy matter; all our resources and skill and ingenuity will be taxed in achieving it, and rarely is it granted, even to Nature herself, to produce anything that is entirely complete and perfect-in-itself.” 20

Thomas Cole, ‘Architects Dream’, (1840)

American historian Marvin Trachtenberg discusses this as becoming the dominant mindset in Western Architecture:

“Alberti categorically rejected this ubiquitous method, opening an unbridgeable chasm between designing and building (the one, in fact, that we live with today). In his ideal architectural world, in absolute antithesis to contemporary practice (as well as his own eventual work as an architect rather than writer all of the learned, extended, redundant, and comprehensive planning and replanning preceded construction. Any changes during execution were ruled out.” 21

Indeed Alberti proposed (although contextually one could argue with some sense of irony):

“...We may determine in advance what is necessary and make preparations in order to avoid any hesitation, change, or revision after the commencement of the work...” 22

By casting ‘perfect’ architecture as necessarily immutable, Alberti arguably was successful in positioning architecture's opposition to time as the necessary foundation of the mindset of the architectural profession. This understanding of time as an inherently negative destructive force, ‘time the destroyer’, was a significant break from the long-dominant cultural construction of time as a positive, creative force that had been dominant in the ancient and mediaeval periods. Within which while the latter encompassed an expectation for a building to be modified whilst it was still being constructed and even after it was ‘finished’, the antithesis of Alberti’s ‘great building’ required no change once drawings were complete. 23 24 25

Alberti cast his architectural reasoning of the ‘great perfect building’ as being in step with nature’s ability to create fully formed ‘perfect’ assemblages. This contrasts strongly with the classical reasoning of nature that saw constant change as inherently ‘natural’ and as part of the ‘essence’ of things. Trachtenberg highlights this poignantly by comparison to Ovid’s epic poem Metamorphosis (8 CE) with the lines:

“My mind is bent to tell of bodies changed into new forms”... “Whatever is beneath the heavens change their forms, the earth and all that is within it.” 26

Architectural philosopher Karsten Harries contrasts the organic approach of the Baroque with the ‘classical’ approach also apparent in Modernism:

“The former invites metaphors that suggest absence, change, life, time; the latter invokes metaphors that suggest presence, stasis, death, eternity.” 27

According to Trachtenberg, Alberti’s reasoning for the denial of time in his architecture is seen as an attempt to create a humanistic power over time. That is, for the architect as an individual to shape and control it, rather than be subsumed by it. The ability for the expansion of the temporal through design, the compression of the temporal through the production of architectural artefact and finally a collapsing or reversal of time, or an architecture of duration through the apparent immutability of the final ‘perfect’ object granted the illusion of power to the author and in doing so Alberti presents what appeared to be a methodology for building against time. 28

What may be of interest here is that Alberti understands the need for a durational approach within the construction of ‘great buildings’. He states that for proper construction, time must be taken to ensure both the materials and the technique are of the ‘appropriate’ duration. This somewhat paradoxical view of the operation of building as durational has been linked by Trachtenberg to Alberti’s humanist tendencies; Alberti understands the negative force of time ‘on the lives and works of men.’

Indeed Alberti’s final book in the treatise talks about restoration, decay and ruin of works, and the irrevocable destruction of architecture. For Alberti the terror of time is that it negatively impacts every aspect of ‘great building’, and it is only in the careful and measured design of architecture that time can play any positive aspect before it is resisted at all costs. 29

With Alberti’s treatise and influence we see the abandonment of a durational reasoning that had lasted and served architecture from Antiquity through to the Renaissance. The reverberations of the desire for an ‘immutable architecture’ continued to be felt from Alberti’s time, through to the Modernist Bauhaus Movement and Gropius’s call for ‘the complete building’ which still manifests today with the deeply problematic notion of building ‘against’ time rather than ‘with time’. 30

The Terror of Time

“Architecture is not only about domesticating space, It is also a deep defence against the terror of time, The language of beauty is essentially the language of timeless reality.”

Karsten Harries, Building and the Terror of Time, 68. 31

When we consider Alberti’s approach to foster an ‘immutable architecture’ or to build ‘against’ time, we know that he is reacting with fear to the durational finitude of not only architecture as artefact but also the mortality of man. German architectural philosopher Karsten Harries elaborates on this point in his seminal work Building and the Terror of Time (1982), in which he advocates for an architecture in tune with the temporal. For Harries, mankind’s utilisation of architecture as a tool to defy the psychological effects of time are apparent. Harries traces shelter as the most fundamental way to provide a protection from times of terror, to banish those feelings of vulnerability and mortality.32 Harries elucidates:

“Building has been understood to be a domestication of space. To domesticate space is to tame it, to construct boundaries that wrest place from space. Such construction receives its measure from our need to control the environment. Control should not be understood here too narrowly: it is not just a matter of creating an artificial environment that offers protection against an often unfriendly world; as important as physical control is psychological control.” 33

Furthermore, Harries goes on to state the innate relationship between man, architecture and time:

“Talk of architecture establishing place by the construction of boundaries in space suggests a quite traditional distinction between arts of space and arts of time, between formative and expressive arts. The distinction has a certain obviousness; yet our experience of space and our experience of time are too intertwined to allow us simply to accept it. Thus, if we can speak of architecture as a defense against the terror of space, we must also recognize that from the very beginning it has provided defenses against the terror of time.” 34

We see here a connection to French philosopher Gaston Bachelard on the primitiveness of refuge in The Poetics of Space (1958):

“Well-being takes us back to the primitiveness of the refuge. Physically, the creature endowed with a sense of refuge huddles up to itself, takes to cover, hides away, lies snug, concealed.” 35

Harries ties this instinctive desire for shelter against time, with Bachelard’s notions of comfort derived from memories of protection. Here we link ideas of shelter to memories of stasis, safety and control. The enclosure becomes the psychological protection from change. Nostalgia and memory replace the uncertainty of external existence. 36

Harries explains that the symbolism inherit to the temple, church or house creates a repetition of ‘divine archetypes’. Through the act of worship or dwelling, man is able, albeit illusionary, to become atemporal and escape the terror of time. Indeed of all the typologies, the house comes to signify a unique position in the lives of its inhabitants. 37 Romanian historian Mircea Eliade states the fundamentally natalist view of the house

“A ‘new era’ opens with the building of every house. Every construction is an absolute beginning; that is, tends to restore the instant, the plenitude of a present that contains no trace of history.” 38

One of the ever-returning concepts in relation to architecture and time is the notion that as architecture continues to develop, it is consistently cast in opposition or resistance to what seems the changing state of ‘nature’ or in less secular-times ‘the divine’. The notion that architecture can provide an escape from the flux and chaos of the natural world is not new.

Pieter Bruegel, ‘The Tower of Babel’, (1563).

For Harries the greatest mythical analogy is that of The Tower of Babel. Here we have an artifice born of man's pride that seeks to challenge the divine and in doing so extol their mastery over both the physical and spiritual world. Harries points to Bruegel's painting as showing man trying to dominate not only space but also time, and in doing so revealing his total inability to do either. 39 The building continues ever forward as previous iterations crumble, decay and return to the landscape. On the small dwellings built into the side of the tower Harries has this to say:

“Against the tower itself modest shelters nestle much as buildings may nestle against some city wall or church in a mediaeval city.

Here we have, not monuments, but buildings that speak of a very different, less antagonistic relationship to time. They hint at possibilities of dwelling born of a trust deeper than pride. Such trust demands determinations of beauty and building that do not place them in essential opposition to time.” 40

It’s potentially here that an antidote might be found for the antagonistic building ‘against’ the terror of time, architectural historian Karen Franck interprets Harries view particularly in relation to Babel:

“For Karsten Harries, Bruegel’s painting illustrates the prideful desire to resist time by constructing monumental buildings that dominate time and space, but also another human desire: to create modest, human-scaled structures that are responsive to their neighbours, as shown nestled against the tower and making up the city below.” 41

The Lives of Buildings

“A building lost is never regained.

That is perhaps the strongest argument for proceeding cautiously and assuring that the difficult decisions about what to save are not made in response to the short cycles of taste and fashion.”

Paul Goldberger, Why Architecture Matters, 2009. 42

There is a view that architecture is inheritably ‘natalist’, fixated on the ever-increasing production and eventual discarding of built artefacts and edifices. This notion of a genealogy of architecture that in fact only has the binary existence of ‘alive or dead’ before issuing a plethora of offspring is problematic. As Charles Jencks would formulate and formulate time and time again, architecture may develop over time and bifurcate due to cultural or technological change, however this in and of itself is not the same as biological reproduction. Reacting against Alberti’s dominant ‘immutable architecture’, there are a multitude of ways architecture can be a process that reacts to and with change, evolving and extending over time rather than being artificially encapsulated by what appears a perpetual moment, a stasis in time.43

In a practical sense ‘The Lives of Buildings’ does not merely refer to a binary state of ‘alive or dead’ but rather the multitude of differing existential states. From a tectonic sense there is little reason why architecture can’t be infinitesimally mutable and changing, as Arup researcher Steven Groák describes as:

“An open and unstable system composed of flows of energy and matter.” 44

Or perhaps more fatalistically as Stephen Cairns and J.M. Jacobs put forward in their work Buildings Must Die: A Perverse View of Architecture (2014):

“[On Architecture] It has lives as well as a death – an ending that can also be designed in advance.” 4

Architectural theorist Jill Stoner has set out in her text The Nine Lives of Buildings (2016) possible definitions for the varying states of ‘architectural lives’ and how these affect the temporal nature of all architecture, they are as follows. 46

i) Abandonment

Stoner argues that abandonment becomes the oldest and most ‘natural’ state for a building once it has outlived its intended purpose. The power of the site of abandonment is tied not only to what architectural form or ruin remains but rather the echo back of a collective memory of place. The act of separation of place from a time of use is significant. As Stoner elaborates:

“Sites of abandonment tend to embody the stories that rendered them obsolete, whether from failing economies, political upheavals or nuclear disasters...These buildings acquire character [and by extension a new form of place]; they become witnesses to the slow motions of time, and prophecies of possible futures.”

ii) Demolition

The power and the fury of the wrecking ball: demolition reflects a more wasteful enterprise of the built environment. As architecture has become a mass commodity that proliferates the landscape, Stoner sees a classical example of demolition in the urban renewal and slum clearance of the 1950’s-60’s within the United States. Consecutive post-war waves of demolition and new building were seen as ‘the bell that cannot be unrung’. For stoner the rupture caused by demolishment ‘removes potential and revokes any future; a demolished building’s second act as landfill offers little possibility for any life beyond its first.’

Author Unknown, ‘Demolition of Pruitt-Igoe’, (1972). Pruitt-Igoe, St. Louis, USA. Minoru Yamasaki 1951-1972/76

iii) Deconstruction

In comparison to demolition, deconstruction comes as the systematic dismantling and salvage of a building’s components, thus keeping them, as Stoner says, ‘alive for future use’. Not purely an outcome of Anthropocene age economics, deconstruction is an ancient method for interacting with architecture. The removal and replacement of materials to create entirely new architectures has been prevalent for as long as man has been building.

iv) Preservation, Conservation, Restoration

The act of preservation, conservation and restoration places an inherent value judgement on any particular piece of architecture. This represents an echo of Alberti’s perfect building. However, all three methods speak directly to combating (or in the case of restoration) attempting to revert the mark of time on physical form. This protection against time is generally tied to cultural understandings of an architecture of a particular time or related to a particular event. As Stoner puts forth, ‘as a strictly material art, preservation and restoration are independent of use.’

v) Renovation and Rehabilitation

Remaking what is seen to be a dilapidated building, renovation and rehabilitation occupy a space of differentiation from Stoner’s definition of preservation, conservation and restoration. The cultural or architectural significance may play no part in the reasoning for rehabilitation. Rather the act is to make the architecture fit to purpose, whatever that may be. Here we see not necessarily an attempt to reverse time but rather to reset the clock all together in what can become nothing more than a facsimile of what once stood in its place.

vi) Adaptive Reuse

The increasing trend of adaptive reuse sees a building or site redesigned and modified to suit another purpose altogether. As with conservation the cultural significance of a building may be retained even if the original function is drastically altered. However for Stoner, adaptive reuse is often an act of economically motivated rather than done in the name of nostalgia or cultural preservation of place.

vii) Reoccupation

As with adaptive reuse, reoccupation looks at the recovery of abandoned architecture. This can be done in a much more informal nature, rather than with what Stoner calls ‘preservationist pretence’. A significant determinant of whether something is ‘reoccupation’ is its inherent unsanctioned and provisional or ‘socially fragile’ nature. Stoner points to this perhaps being the oldest form of recovery of abandoned architecture.

viii) Pure Expression:

For Stoner ‘Pure Expression’ comes to be the artistic expression or intervention either ‘aggressively temporary’ or ‘enduring for a millennia’. In this way, the physical act of transformation acts as a ‘call to attention’ of a ‘transformative moment in time.’ Appropriation, and totally discarding architectural and convention, becomes a powerful artistic tool of commentary.

Ezra Orion, ‘Tribute in Lights’, (2010).

viii) Resurrection

The final category given by Stoner relates to the recreation either as piece or in total replication of an architecture that has all disappeared. Here is an echo of that call for immortality of architecture, often in a symbolic simulacrum rather than facsimile. A powerful example Stoner gives is the ‘Tribute in Light’ which occurs every year on the anniversary of the 11th September destruction of New York’s Twin Towers and entails two beams of light that act to replicate the since-disappeared silhouettes of the iconic buildings.

The removal of a building can have profound consequences. As is the apparent nature of time, once gone, they can never truly be recovered. If as theorist Paul Virilio once wrote ‘the invention of the ship was also the invention of shipwreck’, surely the invention of an architectural work is also the invention of its eventual architectural ruin. 47 Along these lines, it should come as no surprise that the image of ruin is such a powerful motif for architects and laypeople alike. The American sculptor Robert Morris stated the power of the ruin in The Present Tense of Space (1978) as such:

“Approached with no reverence or historical awe, ruins are frequently exceptional spaces of unusual complexity, which offer unique relations between access and barrier, the open and the closed, the diagonal and the horizontal ground plane and wall. Such are not to be found in structures that have escaped the twin entropic assaults of nature and the vandal.” 48

Andreas Huyssen in her text Nostalgia for Ruins (2006) traces the ‘cult of ruins’ in dominant Western discourse from the time of the enlightenment up until contemporary times. More powerfully she speaks of the language of ruins in recent times and their relationship to evolving ideas surrounding modernity:

“The cult of ruins has accompanied Western modernity in waves since the eighteenth century. But over the past decade and a half, a strange obsession with ruins has developed in the countries of the northern transatlantic as part of a much broader discourse about memory and trauma, genocide and war. This contemporary obsession with ruins hides a nostalgia for an earlier age that had not yet lost its power to imagine other futures. At stake is a nostalgia for modernity that dare not speak its name after acknowledging the catastrophes of the twentieth century and the lingering injuries of inner and outer colonization. Yet this nostalgia persists, straining for something lost with the ending of an earlier form of modernity. The cipher for this nostalgia is the ruin.” 49

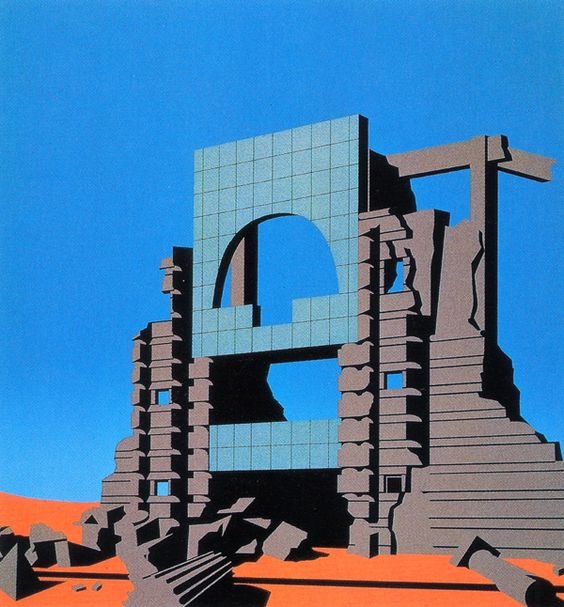

Arata Isozaki, ‘Tsukuba Center’, (1979).

Returning to Karsten Harris’s notion of architecture as attempting to placate ‘the terror of time’, he puts forth the ruin as the most obvious ‘counterimage’ to this form of architecture. Here the comforting images of permeance and the nostalgic memory of refuge are replaced with a physical artefact which acts as a testament of the failure of the architect to stave off this terror. However, the silver lining in the image of the ruin for Harris is the notion that it can call for reflections on the vanity of human building and the sublime power of nature. Human construction here appears to surrender itself to space and time.’ 50

The humanistic aspect of the ruin can become a powerful architectural device that speaks with the past, present and future. As a recurring example in the oeuvre of a single prominent architect, architect-theorist Juhani Pallasmaa in Hapticity and Time – Notes on Fragile Architecture (2000) explains how the architectural language of fellow Finnish architect Alvar Aalto’s mid and late period work works in a humanistic way to deal with the temporality of the ruin:

‘An explicit device of Aalto’s for capturing a sense of time is the image of a ruin. He utilizes explicit or subliminal images of ruins to evoke a melancholic experience of the past, and of the inevitability of erosion, decay, and death. Aalto juxtaposes images of permanence (stone, brick) with images of transitoriness and loss (erosion, climbing plants and the patina of mold).

Even the changing of light concretizes the passing of time. Opposed to the mechanical imagery of a machine process, the materials that Aalto uses express a humanizing touch of a skilled hand. Aalto’s attitude reverses the modernist ideal, which sought to give a machine appearance even to components produced by hand.” 51

For Pallasmaa the way Aalto utilises architectural gestures throughout his oeuvre is an exemplar for a successful methodology of transcending the negative aspects of time and instead utilising them as positive architectural drivers. Here the utilisation of the passage of time as a manifested architectural aesthetic across a multitude of durational tectonics enlivens the architecture so that in return it may come to live its many lives.

Etienne-Louis Boullée, ‘Cénotaphe à Newton’, (1784).

On Geometry, Cosmos and ‘Timeless Architecture’

“Form is nothing else but a concentrated wish for everlasting life on earth.”

Alvar Aalto, Alvar Aalto, the Early Years, 192. 52

The power of geometry lies in its ability to generate powerful emotional responses in those who perceive it. Whether this is an innate as that of an archetype, purely perceptual as with gestalt theory or a learned response is not entirely relevant. Geometry has the ability through simplicity or complexity to seem ‘true’ or ‘sacred’. It has been described this way since before the time of Plato. Naturally within architecture it also presumes a dominant position as a tool for use by the architect. Geometry’s seemingly memetic ability to generate its own mysterious mythology in regard to time; take for example Le Corbusier’s fable of the origin of building, his primitive builder insists on simple geometric forms, as they are to endow what he builds with that aura of reliability that seems to protect against time. 53 Karsten Harries utilises the example of two lines in relating the power of geometry against his concept of ‘the terror of time’ as such:

“Take two lines: one dashed off, restless, resembling handwriting; the other a circle, constructed with the aid of a compass. The two stand in very different relationships to time. The former has directionality; we can speak of a beginning and an end. The latter gestures beyond time; in its self-sufficient presence it comes as close as a visible form can to the timeless realm of the spirit.” 54

Karen Franck interprets this as an attempt to cope with Harries ‘terror of time’ by ‘spiritualising the environment.’ She goes on to state:

‘Simple geometric forms, straight lines, right angles, regular polygons, such as a circle drawn with a compass, come ‘as close as a visual statement can to the timeless realm of the spirit, while an ‘expressive squiggle’ has an organic look and seems to embrace time.’ 55

This utilisation of geometry to generate form comes to be a tool for the interpretation of the value of architecture and particularly its aesthetic characteristics. Take this foundational extract on geometry, form and beauty from Plato’s Philebus (360-347 BC):

“I do not mean by beauty of form such beauty as that of animals or pictures, which the many would supposed to be my meaning; but, says the argument, understand me to mean straight lines and circles, and the plane or solid figures which are formed out of them by turning-lathes and rulers and measurers of angles; for these I affirm to be not only relatively beautiful, other things, but they are eternally and absolutely beautiful, and they peculiar pleasures, quite unlike the pleasure of scratching. And there are colours which are of the same character and have similar pleasures.” 56

Returning once more to Harries we see a contrast between the appeal of organic geometry as being ‘in step’ with time against inorganic geometric forms that belong rather to the sacred realm of the spirit rather than the body. For Harries a defining feature of sacred geometry is the difficulty of recreating without tools (the example of utilising a compass to draw a circle is given) to show how such simple, yet complex to generate, geometry is literally out of reach of the corporeality of the body. 57 This recurring theme that links geometry to sacred space and therefore the repudiation of time in place of the eternal also has strong architectural links to the development of a language of modernity. French Enlightenment architect Claude Nicholas Ledoux was seemingly fascinated with the power of simple geometric forms. In his refusal to submit to what could ostensibly be called Vitruvian doctrine of ‘the art of building’, he rather claimed that:

“The first principles of architecture are to be discerned in symmetrical solids, such as cubes, pyramids, and, most of all spheres, which are the only perfect architectural shapes which can be devised.” 58

For some prominent architectural historians such as Emil Kaufmann the ideas and hyperreal designs of Ledoux and Boullée alongside others such Violette-Le-Duc became a fundamental foundation for the later development and acceptance of Modernist Architecture. 59 Returning to Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, we see how he located geometry and form as part of the mental task of architecture in relation to Harris’s ‘terror of time’, Aalto concluded early in his career that:

“Form is nothing else but a concentrated wish for everlasting life on earth.” 60

A similar vein of reasoning is carried on by Austrian postmodern architect Hans Hollein, who reiterated in Absolute Architecture (1968):

“Architecture if a spiritual order, realised through building. Architecture - an idea built into infinite space, manifesting man’s spiritual energy and power, the material form and expression of his destiny, of his life. From its origins until today the essence and meaning of architecture have not changed. To build is a basic human need. It is first manifested not in the putting up of protective roofs, but in the erection of sacred structures.” 61

This notion of cosmogony and ‘divine building’ alongside sacred geometry and form seeks to cast the architect and by extension man as the promethean creator of tangible timeless ‘spiritual space’. Through the act of construction this ‘cosmic’ manifestation can take place. Harris sees this as a self-fulfilling prophecy in relation to this ‘timeless’ aspect:

“Building can help to establish or to reinforce such interpretation; a building that presents itself as an imitation of divine building can claim to give temporal existence its proper measure and foundation.” 62

Despite this highly spiritualised notion of architectural space there have been significant attempts to create a form of taxonomy towards those factors that create ‘sacred space’. One such classification is known as ‘Brills Approach’ which sets out the following fourteen methods for the creation of ‘sacred space’. 63

i) Making a Location and Center

The creation or acknowledgment of a centre symbolises a reality, versus the non-reality of uninterrupted, homogenous, and formless space. Spaces of quality are, therefore, the physical embodiment of centre on the earth – it is substantial and expressed as a fixed location.

ii) Making Orientation and Direction

Timeless place has an orientation and direction with relation to the centre and each of these directions express qualitative differences. The directions can be expressive of different meanings such as the pleasure of sunrise, the terror of sunset, forward and backward movement, left and right movement, levity towards heaven or downward movement into the chaos.

iii) Spatial Order

The creation of center with subsequent orientation and direction results in the generation of spatial order that is highly valued. When embodied in a sacred place, it signifies victory over the chaotic space. Sacred places, therefore, reveal the spatial order, suggesting our need for it.

iv) Celestial Order

Celestial order expresses the play of celestial rhythms in space. This order in a sacred place could also be created and based upon celestial references such as the locations and cycles of the sun, moon, stars and winds.

v) Differentiating Boundaries

Each of the boundaries related with the four directions is fixed, clear, distinct, and equidistant to the centre. These boundaries reveal different qualities when compared with each other suggesting symmetry but not sameness.

vi) Reaching Upwards

Spaces of Value are expressive of verticality, signifying a path to the heavens. Verticality is embodied in sacred spaces to subsequently come closer to what is divine. Verticality is articulated in a place by opening it to the sky, or providing soaring walls, columns and the like that reach upward toward the heavens.

vii) Triumph over the Underworld

It is the counter property of reaching downward towards the watery chaos of the underworld. Such a property of reaching downward is conquered through the process of place making. Examples of such situations include sparse water under our control, for example; a water fountain, shallow still pool or cistern, an ordered garden that is bordered and controlled.

viii) Bounding

Bounding expresses differentiation and defines the distinct domain of an ordered cosmos from the chaos. Boundaries are, therefore, distinct, and articulated in three-dimensional space in the form of walls, floors, and roofs. Of these three, the roof is most expressive of our desire to reach the divine.

ix) Passage

Passage is achieved through dematerialisation of staunch wall boundaries and is embodied in such a manner that one is able to enter and leave a certain space; it forms a continuity and means of communication between the two opposing domains present inside and outside the space. It is typically large in size to accommodate the divine and godly enhancement that occurs on exit from sacred place.

x) Ordered Views

The importance and significance of passage is maintained by restricting views between two realms of space that can be called sacred and secular, divine and ordinary, valuable and ordinary. This enables a sacred space to sustain and reinforce its sacristy and keeps it distinct from the outer world. Direct views between the two types of spaces are avoided. This characteristic is observed through the limited use and specific location of openings such as windows and doorways.

xi) Light

The daily cycles of day and night, being light and darkness, signify an unending cosmic struggle. Light signifies hope with the rising of the sun each day and enables us to experience the changing world. In certain spaces it is symbolic of the passage of time and is typically serving to provide orientation and contrast from the surrounding darkness.

xii) Materials

Light reveals the texture and form of materials in a sacred place. The materials that make up valuable spaces are symbolic of the cosmic struggle and victory over the chaos. Therefore, building materials used suggest a certain quality of expression, the selection and placement of materials indicate the presence of this quality. These materials are resistant to erosion brought about by natural forces and maintain their formal integrity and physical order.

xiii) Nature in Our Places

An important feature of quality in a space is that it contrasts with the disordered vastness of nature surrounding it. Nature maintains its natural spirit, but is subdued, controlled, bordered, ordered and tamed. In this sense, nature is constantly cared for, controlled and ordered, signifying the image of balance and taming the chaos.

xiv) Finishing a Place

The act of creating an architectural space signifies an absolute beginning – it is a divine repetition of the creation myth or the creation of the world. Therefore, ritualistic and consecrate acts and ceremonial celebrations mark the act of completion of the building. Such ceremonies signify the reality and enduringness of our efforts in finishing the place for habitation or any other function.

In contrast to the aforementioned intersections between time, architecture, geometry and sacred space there is the viewpoint of Japanese architect Toyo Ito who attempts to bridge the perceived gap between nature and architecture. The benefit of man through the acknowledgement of the profound power as well as the flaws in classical or pure geometry and the orthogonal grid which Ito see’s as being antagonistic to the ‘world of natural phenomena’. Rather than the classical order, Ito utilises an organic-fluid order of change which is ‘relative, flexible and soft’. Rather than the rigidity of immutability, such an architecture can be influenced by external factors and reacts to change and flux rather than outwardly resisting it through artifice. 64

Tadao Ando, ‘The Hill of the Buddha’, Sapporo, Japan. (2015).

On Timeless Architecture

“What was, has always been. What is, has always been, and what will be, has always been. Such is the nature of beginning.”

Louis I. Kahn, What Will Be Has Always Been: The Words of Louis I. Kahn, 1986.65

The notion of ‘timeless’ architecture is a nebulous and somewhat deceptive descriptor. In definition, architecture which is considered ‘timeless’ is of a calibre that seems to remove it from any singular time, in a way transcending style and taste. We know that this is an impossibility, for all architecture regardless of how far reaching its effect may be is a product of not only it’s time and place but also of the rich genealogy of cultural and architectural development that preceded it.

The second charge of ‘timeless’ architecture is that it manages to evoke an eternal, everlasting, permanent state. In effect ‘timeless’ architecture is called that for its apparent rejection and domination of time itself. On the face of it, calling a work of architecture ‘timeless’ is in fact placing high value on architecture by associating it with the impossible architecture, Alberti’s ‘immutable architecture’ that will persist and remain in some respect seemingly forever. 66

In architect and theorist Sally Essawy’s analysis ‘The Timelessness Quality in Architecture’ (2017) she highlights the following aspects that contribute to the perception of ‘Timeless Architecture’: 67

i) Darkness and Light

The presence of both darkness and light in an architectural space adds a quality of depth to the space, which is not possible with one and not the other. In many examples of ancient architecture, it is sunlight that is utilised to create the timeless qualities; it is the dominant use of natural light and variable darkness that creates the sense of timelessness.

‘Above all else, the beautiful in architecture is enhanced by the favor of light, and through it even the most insignificant thing becomes a beautiful object. Now if in the depth of winter, when the whole of nature is frozen and stiff, we see the rays of the setting sun reflected in masses of stone, where they illuminate without warming, and are thus favorable only to the purest kind of knowledge, not to the will, then the contemplation of the beautiful effect of light on these masses moves us into a state of pure knowing, as all beauty does.’ 68

Louis Kahn on the subject of darkness and light:

‘I would say that dark spaces are also very essential. But to be true to the argument that an architectural space must have natural light,

I would say that it must be dark, but that there must be an opening big enough, so that light can come in and tell you how dark it really is –

that’s how important it is to have natural light in an architectural space.’ 69

ii) Signs of Wear